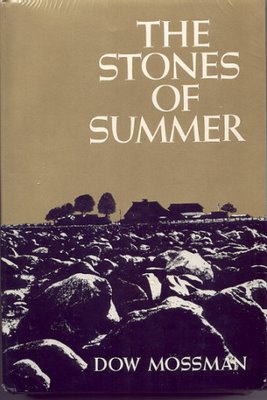

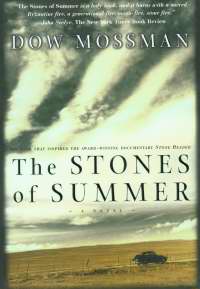

The Stones of Summer, Dow Mossman. Un magistral roman américain, totalement méconnu ici et là-bas, de 1972, date de sa parution, à 2002, date à laquelle un documentaire de Mark Moskowitz, Stone Reader (www.stonereader.net), modèle du genre,a mis cette œuvre majeure sous les feux de la rampe et permis ainsi sa réédition, le livre étant devenu totalement introuvable (La première édition avoisine les 2000$).

Je classe Stones of Summer, aux côtés de Gravity’s Rainbow, des Reconnaissances, de Sur la Route, de La Conjuration des Imbéciles ou de l’Attrape–Cœurs comme un des plus grands romans du XXème siècle. Je pourrais écrire des lignes et des lignes à son propos, évoquer sa structure (Faulknerienne pour les parties se passant dans les années 50, puis glissant peu à peu , insensiblement,vers autre chose pour finir totalement novatrice dans sa dernière partie, se déroulant à la fin des années 60) mais le temps me manquant, je vais laisser la parole à Stephen King et au critique du New York Times de l’époque – ce qui, je l’espère, vous permettra d’aller plus avant. Il le faut. Disons juste, pour finir :

-Que Mossman l’a écrit à 25 ans, et n’a plus rien écrit depuis – il s’en explique dans une lettre bouleversante reproduite dans le McSweeney’s 11.

-Que Joseph McElroy le cite sans cesse : « What a trip , what a testament from the fities and sixties, this life-risking romance with excess and aspiration, defeat and ravishing insight, our maddening American past and its landscapes of lies, laughs, talk, paralysis, rebirth, stony metamorphoses into danger and beauty and story » ; Idem Thomas Sanchez : « A Madhouse distorsion where pain’s cry represents an entire portion of the generation that came of age in the 60’s »

-Que c’est 900 pages de bonheur absolu

-Qu’il faut lancer une pétition pour qu’un éditeur français s’y intéresse.

It's Alive!It's Alive

by Stephen King

The Great American Novel is livelier than ever; and here are three that prove it; just pick the one(s) that fit your hammock.

The Stones of Summer, Dow Mossman : If 20th-century America produced a book of Moby Dick stature, it's probably this one... but don't let that stop you, or even slow you down. All I mean is that like Melville's fish story, this is one whale of a tale that has somehow found an audience in spite of mind-boggling hurgles, including going out of print (Bobbs-Merrill quit doing fiction not long after it published The Stones of Summer in 1972) and only a smattering of reviews. Nor was the author exactly up to a PR tour; when his only book was published, Mossman was still recovering from a nervous breakdown he suffered after finishing his 10-year labor of love/hate.

The novel is difficult to get into - the first 30 pages read like an extended set of Bob Dylan liner notes from 1965. But then pure narration takes over, and readers are treated to a magical mystery tour of adolescent life in America's heartland during the '60s. Because Mossman is a poet as well as a crack storyteller, the result is both lyrical and gripping: Think Jim Morrison crossed with J.D. Salinger. Oh, and sometimes it's fall-on-the-floor funny, too.

Once you've read the book - which takes some doing - treat yourself to Mark Moskowitz's documentary Stone Reader, which played a pivotal role in bringing this forgotten book back into the cultural mainstream. Reader (available on DVD) chronicles Moskowitz's search for Mossman, who dropped from view 30 years ago. It's also a love sonnet to books and reading

The Stones of Summer

A Yeoman's Notes, 1942-1969

By Dow Mossman

552 pp. New York:

The Bobbs-Merrill Co. $9.95

By JOHN SEELYE

"The Stones of Summer" cannot possibly be called a promising first novel for the simple reason that it is such a marvelous achievement that it puts forth much more than mere promise. Fulfillment is perhaps the best word, fulfillment at the first stroke, which is so often the sign of superior talent and which is also a frightening thing, for the author may remain forever awed by the force and witness of his first production. I don't think, however, that this will happen in the present instance. Dow Mossman's novel is a whole river of words fed by a torrential imagination and such a source is not likely to stop flowing.

In an age of thin books and overblown copy, this forceful, expansive talent is a welcome sign. I am afraid that the size (and price) of "The Stones of Summer" will go against it, however, and it also lacks that punchy, journalistic, eventful quality of popular, marketable, reviewable fiction -- whether "Airport" or "Deliverance" -- does not make much difference. "The Stones of Summer" is a novel in the classic sense, not merely a novella narratio, a new kind of story, a news event, material to be shredded in the chattering machines of journalists, but as something more solid, more closely approaching that other (not etymoligically related) "novel," that legal term in Roman law pertaining to a new order, a new way of regulating things. For me at least, reading "The Stones of Summer" was crossing another Rubicon, discovering a different sensibility, a brave new world of conciousness. "The Stones of Summer" is a holy book, and it burns with a sacred Byzantine fire, a generational fire, moon-fire, stone-fire.

By this I don't mean that a lot of ho-hum tripping goes on in "The Stones of Summer," or that this is another mother-acid book, like "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" or "Trout Fishing in America." I do mean that this book could only have been written by a member of that nearly missing generation which from time to time reaches out to us from that other dimension to which they have journeyed. The autobiographical hero, Dawes Oldham Williams (D.O.W.), smokes a joint from time to time, and according to an autobiographical novel he is writing, once blew his mind right into the Cuckoo's Nest by means of a triple-decker toke, and is suffering a consequent disorientation which some call schizophrenia, others truth. But the taking of dope is no issue here, having little relevance. What I am talking about is the evident impress of an entire generation's experience on the ordering of form, the fasioning of style, the entire business of putting so complex a novel as "The Stones of Summer" together.

Thus the opening section of three, "A Stone of Day," which concerns two years in the life of Dawes as an eight- to nine-year-old, reads like William Faulkner might have written had there been something in in that ol' jug besides likker. Take a specimen slide from the first paragraph of the book: "When August came, thick as a dream of falling timbers, Dawes Williams and his mother would pick Simpson up at his office, and then they would all drive west, all evening, the sun before them dying like the insides of a stone melon, split and watery, halving with blood. August was always an endless day, he felt, white as wood, slow as light." Or, as Dawes and his family drive east across Iowa to his grandparent's farm, where his grandfather, Arthur, raises greyhounds: "In the dark now, as he was driving toward them, they would be all around him, Arthur, who was bent against them, on the long edge of their motion, within their dense and furious dog sounds, their whimperings and frantic invocations."

This is the Faulknerian swarm miasmic, given order not by the baroque turbulence of Jacobean Gothic, but by the whining rise and fall of a ceaseless sitar. Get that sun like a "stone melon"! Falkner never split a melon quite like that one, you can bet.

As in Joyce's self-portrait, the style changes as Dawes matures. The Faulknerian cast of the opening third, warranted by the scene -- an agrarian America cursed by the unexorcised ghosts of ancestral sites and seething with repressed violence -- is reduced considerably in the second section, "Stones of Night," which concerns Dawes's adolescence. Where the child is something of a mystic, most at home in the wildness of nature, rebelliious against Grandftather Aruthur's mean-sprited tyranny, in the second section this mysticism takes on an anti-social bent, and Dawes becomes a malcontent, less a prohpet than a teller of unwelcomed truths. Since he is hardly the Artist as Sensitive Plant, but plays football, pool and poker, necks, pets and yearns to fornicate, and drives an old car which is a battered symbol of alter ego, he is thrown in with a gang of the usual mixed American stripe, which generally rewards his insightfulness with a fistful of his own teeth.

The Dawes of this section is largely a comic figure, mostly unsuccessful in all that he attempts, and the atmosphere throughout is hilariously comical, for his gang has a taste for outlandish escapades and violent pranks. The result is rather like "The Last Picture Show" crossed with "Penrod and Sam," and very, very funny. And very accurate, as well, even when tinged with Faulknerian surrealism.

Where McMurty, the Grace Metalious of the Planes, comes on with the specious realism of soap operatics, a flat style evoking a flat landscape and mostly flat women with boys on top of them, the ebullience of Mossman's acrobatics succeeds in conveying the rebellious energies of youth, the essential madness of adolescent reality. As in real life, no generous, but defeated, yet kindly and still rather pretty, if trearful, wives offer their bodies to these boy. Most older women here are mothers, and they always come into the room at the wrong time, and are universally a pain.

This second section ends with an auto crash in which most of Dawes's friends are killed. He is the sole, accidental survivor, and henceforth his friends, like his ancestors, will haunt him. They have drowned in the Mississippi, and Dawes in the final third of the novel, "The Stones of Dust and Mexico," increasingly takes to himself his favorite indentity, Huckleberry Finn. Not the Chuckleberry of the early and late episodes of Twains's book, but the other Finn, the anti-hero, the sterling picaro of the mocking epic at the center -- the water-borne part. Ragged, dirty, unkempt, eternally rebellious, battered from poolcues and fists, a sort of WASP Schlemihl, Dawes persits in imposing his self-defined role in saintly malcontent upon the world, which sewards him as all truthwriters are rewarded, by grinding him slowly to bits.

It is here, in this final section, that the style -- like Dawes himself -- begins to come apart. The structure is discontinuous, circumambient, lost in time and space, an eternal bummer to Mexico and death. Long stretches are filled with quotations from Dawes's novel in progress, fragments from his notebooks, letters from his best friend in Vietnam. Flashbacks explode with flashbacks, fading eventually to a regained moment in the narrative. The sensuous flow of the opening section and the inspired mayhem of the middle are missing.

There is a great deal of intellectual foreplay here, which some may find irksome, but which I felt a magnificent display of juggleing. Such matters are invariably hostile to the flow of narrative, yet Mossman, by sheer wizardry of style, keeps them moving. And these literary allusions, along with the pop culture detritus afloat in the second section of the novel and the occasional political references in the third, form an important aspect of the novel, part of its intended form.

For if this novel has a quality of greatness, and I think that it does, that quality is related (as it invariably is) to a great tradtion, that mad, Dionysian stream that D.H. Lawrence perceived flowing through certain classics of American literature, but that (as Dow and Dawes both see) flows most strongly through the adventures of Huckleberry Finn -- a Huck, as Dawes insists, who smoked something other than tobacco in his corn-cob pipe. Is there a moral to this story, this magical tale of rolling stones and singing stones, stone tongues and stone lights, this stone fishing in America? I don't know, and even if I did, I wouldn't say. Let me conclude, rather, with something by way of tribute to this very talented writer, an invocation of that moment of absolute silence that follows when you have finished the last chapter, paragraph and word of a book which you greatly admire, and set it aside so as to hear your own inner echoes, the dying chord of sympathetic response.